This article is a direct continuation of Rethinking Packet Networks in Amateur Radio. In the first article, we argued that many assumptions inherited from the Internet (continuous connectivity, low latency, conversational protocols) do not hold in real-world amateur-radio environments. Especially in RF systems operating under interference, mobility, duty-cycle constraints, or regulatory limitations, packet networking often fails in subtle but fundamental ways.

This second article explores Delay-Tolerant Networking (DTN) as one possible architectural response to these limitations.

The goal is not to present DTN as a universal solution, nor to introduce yet another buzzword into the amateur-radio vocabulary. Instead, the aim is practical: to understand what DTN actually is, why it was designed, and how its principles could relate to the realities of amateur-radio and RF networks.

Readers unfamiliar with DTN are strongly encouraged to read the DTN Tutorial by Warthman et al. before continuing. It is concise, clearly written, and provides an excellent overview of DTN architecture and terminology. Likewise, Kevin Fall’s original paper on Delay-Tolerant Network architecture offers valuable insight into the original motivation behind DTN and the problems it was designed to address.

Rather than repeating these materials, this article assumes familiarity with their core concepts and focuses on:

- clarifying common misconceptions about DTN,

- discussing DTN specifically in the context of amateur-radio and RF links,

- and demonstrating a practical, hands-on way to experiment with DTN using real software and a network simulator.

In the following sections, we will first clarify what DTN is not, to avoid unrealistic expectations. We will then examine how DTN behaves in practice, how existing implementations work, and why routing remains the hardest unresolved problem – especially in heterogeneous amateur-radio networks.

1. What DTN Is Not

DTN is often misunderstood before it is even properly introduced. When people first encounter Delay-Tolerant Networking, they tend to interpret it through concepts they already know, such as IP routing, transport protocols, or application-layer messaging. This usually leads to wrong expectations and, later, disappointment.

This section exists to clear the ground. Before discussing how DTN works and how it can be used in practice, it helps to explicitly say what DTN does not try to be.

DTN Is Not a Mesh Network

DTN does not assume that a connected network exists at any given moment. There is no requirement that a path between sender and receiver is available when a message is created, transmitted, or even forwarded.

This assumption was already discussed in the first article as a fundamental limitation of many ad-hoc and amateur-radio networks. Most existing communication systems, wired or wireless, are built around the idea that connectivity exists now, even if it is unstable, intermittent, or asymmetric.

Mesh networks are an obvious example, but they are not the only ones. Traditional packet radio, Hamnet, New Packet Radio, and most IP-based radio systems all rely on routing decisions derived from the current network topology. When the topology collapses or fragments, these systems stop working in predictable ways.

DTN deliberately avoids this assumption. Disconnection is treated as a normal operating condition, not as a failure that must be repaired.

DTN Is Not “Email Over Radio”

DTN is sometimes explained using comparisons to electronic mail or postal systems. These analogies come from the original DTN architecture work and are useful as intuition. Concepts such as asynchronous delivery and delegation of responsibility map well to postal services.

Still, DTN is not an application-layer email system.

In classic email systems, store-and-forward behavior is implemented by applications and servers. The network itself remains unaware of message persistence, delivery responsibility, or retry semantics. DTN takes a different approach. Persistence, forwarding, and custody transfer are part of the architecture itself, not something each application must reimplement.

This matters in radio networks. When every application implements its own buffering, retry logic, timeouts, and failure handling, systems naturally fragment. Each project becomes its own isolated sandbox. Over time, this leads to competing ecosystems, duplicated effort, and ideological splits that have little technical justification.

DTN attempts to move these shared concerns into a common layer, making applications simpler and more interoperable by design.

DTN Is Not Automatically Resilient

DTN is often associated with resilience and disruption tolerance. This association is reasonable, but it can be misleading if taken at face value.

DTN enables resilience, it does not provide it for free.

Reliable operation depends on persistent storage, realistic bundle lifetimes, correct custody-transfer configuration, and an understanding of actual communication opportunities. A poorly configured DTN node can lose data just as easily as a poorly configured router.

What DTN changes is the nature of the trade-offs involved. Instead of assuming continuous connectivity and fast feedback, DTN treats time, storage capacity, and policy as first-class resources.

DTN Is Not a Routing Protocol

DTN does not define how messages should be routed through a network.

It provides mechanisms for transporting and storing data in the presence of delay and disruption, but routing strategy is intentionally left open. Routing decisions may be based on scheduled contacts, opportunistic encounters, probabilistic models, or combinations of these approaches.

This is both a strength and a risk. The architectural principles of DTN can be sound, yet a real deployment may still fail if routing choices are poor.

In heterogeneous amateur-radio environments, routing is in my opinion the hardest unsolved problem. A routing strategy suitable for a low-power LoRa mesh will not work for HF packet radio. Line-of-sight UHF links, point-to-point NPR links, or future data-capable digital voice links such as M17 all require different assumptions and different algorithms.

DTN provides transport and storage primitives. Whether they become useful in practice depends almost entirely on routing.

DTN Does Not Replace Existing Networks

A common misconception is that DTN exists to replace existing networking technologies. It does not.

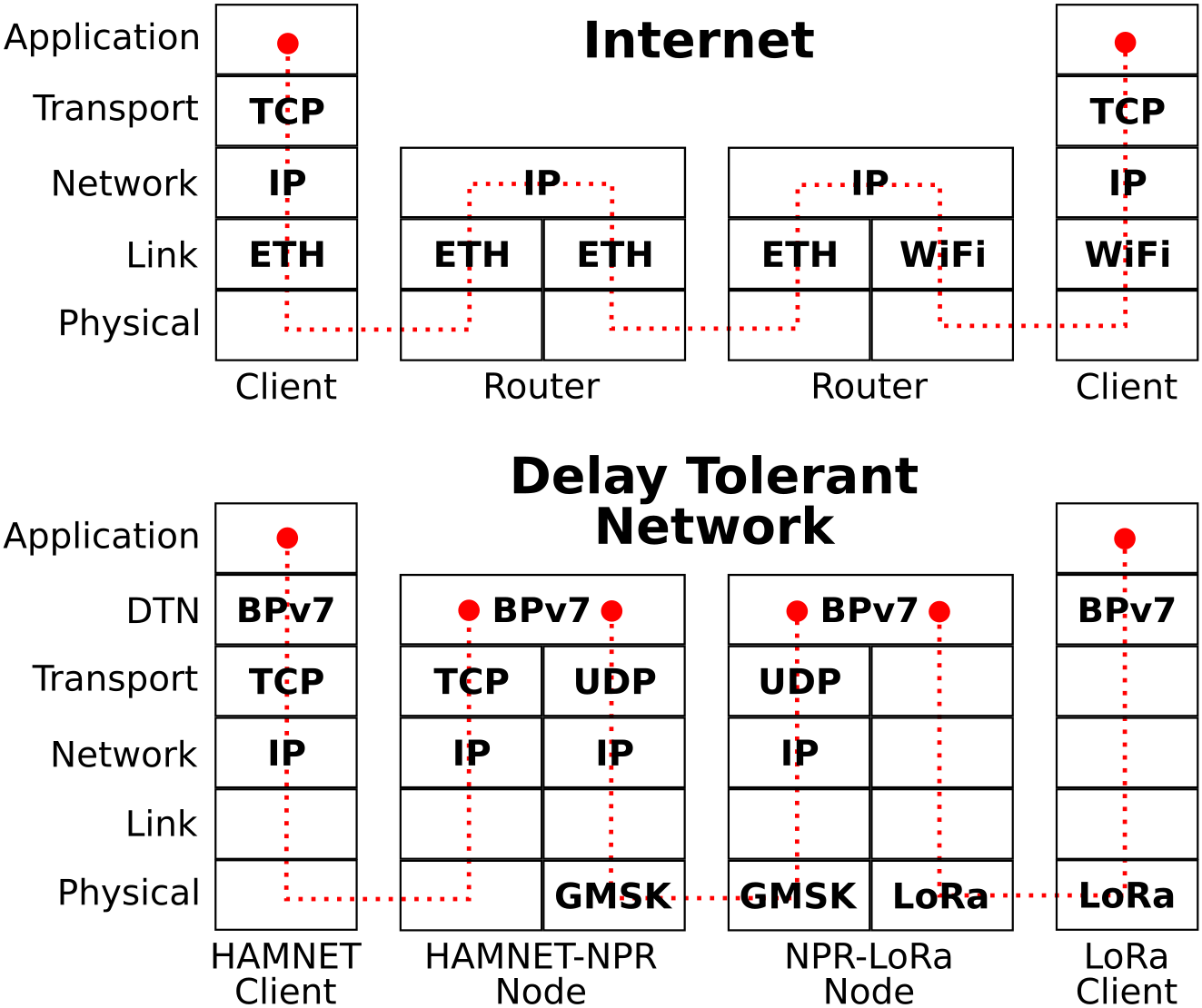

DTN is not a new physical layer, not a new data link, and not a drop-in replacement for IP, AX.25, or any other protocol stack. From a strict OSI perspective, DTN is usually described as an application-layer architecture. In practice, however, it behaves more like a layer between transport and application.

DTN is also not tied to TCP/IP. While many implementations use TCP or UDP as convergence layers, the architecture itself is transport-agnostic. There is no fundamental reason why DTN cannot operate over packet radio, AX.25, custom RF links, or future digital data links such as M17.

DTN Is Not “The Internet, But Slower”

DTN is sometimes misunderstood as a way to run familiar Internet applications over disrupted radio links. In practice, this is rarely true. Most Internet protocols assume interactive sessions, fast feedback, and continuous connectivity. When these assumptions fail, the application experience collapses long before DTN can help.

DTN works best with applications that treat communication as asynchronous message or object transfer. This includes messaging systems that can tolerate delay, content distribution, telemetry, bulletin-board style services, and synchronization workflows designed around eventual delivery.

In other words, DTN solves the transport-and-storage problem under disruption. It does not automatically make existing chatty protocols work over intermittent links. Designing useful DTN-native applications for amateur radio is a major challenge of its own, and likely the next one to address after routing.

2. Bundle Transfer Across a Network

In this section, we look at how a bundle is transferred through a hypothetical amateur-radio environment. The goal is not to describe a currently deployed network, but a technically realistic one that could exist given today’s technologies.

We will be talking about Bundle Protocol version 7 (BPv7), specified in RFC 9171. BPv7 is a concrete, standardized implementation of the DTN architecture and currently the most mature and actively developed one. An older version, BPv6 (specified in RFC 5050), is now considered obsolete and is no longer recommended for new designs.

Consider the following scenario.

A message is created on a computer connected to the Internet, for example via Hamnet. The application does not open a socket to a destination IP address and port, nor does it wait for a reply. Instead, it hands the message to the DTN layer, implemented as a local process, and requests delivery to a remote DTN endpoint.

This endpoint is not an IP address. It is a DTN identifier, a URL-like name defined and used by the DTN network itself. Conceptually, it may look like dtn://ok5vas/message. At this point, the application does not assume when or how delivery will happen.

Initially, nothing unusual occurs. The DTN layer encapsulates the message into a bundle and sends it using a reliable transport. In the Hamnet part of the network, this is typically TCP over IP. From the application’s point of view, the message has left. From the network’s point of view, responsibility for delivery has already shifted to the next DTN node.

The first DTN node acts as a gateway. It accepts the bundle, stores it in persistent storage, and becomes responsible for forwarding it further. At this stage, the underlying transport still looks like a conventional Internet connection. DTN does not replace TCP or IP here, it simply uses them where they make sense.

The situation changes at the next forwarding decision.

The same DTN node is also connected to a New Packet Radio (NPR) link. From the DTN perspective, this is still a single node with multiple possible ways to forward bundles further. A bundle may be received from the Hamnet side, stored locally, and later forwarded toward the NPR network when conditions allow.

How exactly a bundle is forwarded further is a joint responsibility of the DTN layer and the underlying layers. The DTN layer decides which peer a bundle should be forwarded to, based on its routing logic and knowledge about neighboring peers. The concrete details are then handled by the selected convergence layer and the operating system networking stack. For clarity, these internal steps are intentionally simplified here, but we will come back to them later.

From the DTN point of view, this is still a single node. A bundle is received via one convergence layer (a mechanism used by DTN to send and receive bundles over a specific transport), stored locally, and later forwarded via another. The NPR link is not continuously available. Capacity fluctuates, latency can be high, and connectivity may disappear entirely for minutes, hours, or even days. None of this is treated as a failure. The bundle remains stored locally until a contact becomes available, or until its lifetime expires.

When the NPR link becomes available, the bundle is forwarded again. In current NPR deployments, TCP/IP is used on top of the RF link, but this is an implementation choice rather than a requirement. A custom protocol better suited for RF could be used instead. From the DTN layer’s perspective, this detail is irrelevant. The convergence layer adapts bundle transfer to whatever transport exists underneath.

Further along the path, the bundle may enter an even more constrained environment. It could be forwarded into a packet radio network based on AX.25, or into a low-power LoRa network operating under strict duty-cycle limits. At each hop, the same pattern repeats: accept the bundle, store it, wait, and forward it when possible.

There is no end-to-end connection spanning the entire path. No single transport protocol covers the whole journey. At no point does the network assume that the destination is reachable right now. Bundles are not acknowledged end-to-end, but hop by hop, as custody and responsibility for delivery are transferred between DTN nodes.

This difference is illustrated in the accompanying diagram. In the upper part, representing the Internet, the red dotted line shows an end-to-end connection spanning all intermediate routers. In the lower part, representing a DTN network, the red dotted lines terminate at each hop. Each DTN node confirms reception locally and becomes responsible for further delivery.

Eventually, after minutes, hours, or even days, but still within its lifetime, the bundle reaches a final DTN node near the destination. Only there is it delivered to the receiving application. From the application’s point of view, this delivery may appear delayed or asynchronous, but it is explicit and intentional.

This example highlights several important properties.

First, DTN sits above existing transports and below applications. From a strict OSI perspective, it is often described as an application-layer architecture. In practice, it behaves like an overlay between transport and application, providing services that neither layer can offer on its own. In this article, we refer to this layer as DTN, with BPv7 as its concrete protocol implementation.

Second, DTN is not tied to TCP/IP. TCP or UDP are convenient transports where they exist, but DTN does not depend on them. The same bundle can traverse TCP/IP networks, custom RF links such as M17, X.25 packet radio, and low-power LoRa networks without changing its identity or semantics.

Third, time is an explicit part of the system. Delays are expected, persistent storage is required, and forwarding decisions are decoupled from immediate connectivity.

Fourth, DTN naturally handles asymmetric links and heterogeneous data rates. Individual hops may have vastly different bandwidths, latencies, or duty-cycle constraints. A DTN node absorbs these differences by storing bundles locally and forwarding them at a pace suitable for the next link. This prevents congestion from propagating backward and avoids unnecessary bundle loss when transitioning between fast and slow parts of the network.

This is the key mental shift. DTN does not try to stretch the Internet to fit radio networks. It accepts that different parts of the path operate under different rules and provides a common framework to move data across them.

3. Practical DTN Deployments

Before we dive into practical experimentation, it often helps to look at where this technology is used today. Seeing real deployments can help with understanding how DTN works and what it brings.

Delay-Tolerant Networking is often perceived as a purely academic concept, discussed in papers but rarely deployed. This perception is only partially true. While DTN is far from ubiquitous, there are domains where it has been used in real systems for many years, and where its design assumptions closely match operational reality.

Space and Deep-Space Communication

The most mature and long-running use of DTN is in space communication.

DTN concepts originated in the context of interplanetary networking, where long delays, scheduled contacts, asymmetric links, and frequent disconnections are the norm rather than the exception. NASA has been using DTN-related technologies for more than a decade, primarily through the Interplanetary Overlay Network (ION) implementation developed at JPL.

ION implements BPv7 and related protocols and has been used in multiple space and near-space experiments and deployments. DTN technology has been demonstrated on the International Space Station, in space-to-ground experiments, and in various testbeds connected to NASA’s Deep Space Network. In these environments, DTN is not treated as an experimental curiosity but as a practical solution to known and unavoidable communication constraints.

What is important here is not the specific missions, but the operational mindset. In space systems, the absence of end-to-end connectivity is assumed by default. Links are scheduled, contacts are predictable, and storage-based forwarding is a necessity. DTN fits this model naturally.

Terrestrial Networks

Outside of space, DTN has been used more selectively.

There have been deployments and experiments in disaster recovery scenarios, remote sensing, wildlife tracking, and intermittently connected sensor networks (see section 5 of „Delay Tolerant Networks in a Nutshell„). In these cases, DTN is typically used where conventional IP networking fails outright or becomes operationally impractical.

However, it is important to be honest about the scale of these deployments. Most terrestrial DTN systems have been small, experimental, or domain-specific. DTN has not become a general-purpose networking solution for disrupted environments in the way TCP/IP became the default for the Internet.

This gap between technical suitability and widespread adoption is one of the recurring themes in DTN history.

Academic Research

A significant portion of DTN-related work remains in the academic domain.

Much of this research focuses on routing. Since DTN deliberately separates transport from routing strategy, the effectiveness of a DTN network depends heavily on how bundles are forwarded under uncertainty. This has led to extensive research into routing algorithms for intermittently connected networks, mobile ad-hoc networks, vehicular networks, and delay-tolerant sensor networks.

These works explore epidemic routing, probabilistic forwarding, contact-based scheduling, learning-based approaches, and many hybrids. While this body of research is rich and valuable, relatively few of these algorithms have transitioned into stable, widely deployed systems.

For a practitioner, this means that DTN provides solid architectural foundations, but routing remains an open problem that must be addressed for each specific environment.

Why DTN Makes Sense for Amateur Radio

From a technical perspective, amateur-radio networks resemble DTN environments far more closely than they resemble the modern Internet.

As discussed in the first article, amateur-radio links are often asymmetric, intermittent, shared, and constrained by regulation and propagation rather than topology.

DTN, and BPv7 in particular, aligns well with these constraints. It provides a way to connect heterogeneous networks without forcing them into a single protocol stack. Existing technologies such as Hamnet and New Packet Radio already provide relatively stable, high-capacity links. At the same time, other technologies commonly used by radio amateurs, such as AX.25 packet radio, experimental M17 data links, or low-power LoRa networks, are much harder to integrate into a unified system.

The bundle-based, store-and-forward model of DTN offers a way to bridge these worlds. A DTN node can act as a gateway between Hamnet, NPR, and more constrained or experimental radio links, without requiring end-to-end connectivity or uniform link behavior. In this sense, DTN does not replace existing amateur-radio technologies, but provides a framework to connect them more reliably.

At the time of writing, such a DTN-based amateur-radio network does not exist in operational form. This is not a limitation of the architecture itself, but rather a reflection of missing tooling, unresolved routing questions, and the absence of a shared operational model within the amateur-radio community.

These gaps also represent an opportunity.

Before diving into routing strategies or protocol details, it is useful to actually run DTN, observe its behavior, and experiment with failure scenarios. In the next section, we will do exactly that, using a network simulator and an existing BPv7 implementation to explore DTN hands-on.

4. Hands-on: Running BPv7 in CORE

Up to this point, DTN has been described conceptually and illustrated using a hypothetical but realistic amateur-radio topology. To make these ideas tangible, this section shows how to run a working DTN network and observe its behavior directly.

To lower the barrier to experimentation, a ready-to-use Docker image was prepared that bundles:

- CORE Emulator 9,

- a Rust implementation of BPv7,

- npr.xml scenario with preconfigured DTN nodes that start automatically.

All DTN daemons are launched as part of the scenario. No manual installation of DTN software inside nodes is required.

The image and scenarios are available in the following repository: https://github.com/slintak/coreemu-dtn

The setup was intentionally kept simple. The goal is not to simulate RF at the physical or MAC level, but to observe DTN behavior: neighbor discovery, bundle forwarding, storage, and delayed delivery.

4.1 Getting the environment

The recommended workflow is to clone the repository and use the provided Makefile.

git clone https://github.com/slintak/coreemu-dtn

cd coreemu-dtn

To start the environment:

make run

This command pulls the published Docker image (if needed) and starts CORE Emulator. A new CORE GUI window should appear immediately.

If local modifications were made to the image and need to be tested, it can be rebuilt first:

make build

make run

No manual Docker commands or scripts are required or recommended.

4.2 Loading and starting the scenario

Once the CORE GUI is open:

- Open the scenario file

/shared/scenarios/npr.xml - Start the simulation by clicking the green Start Session button

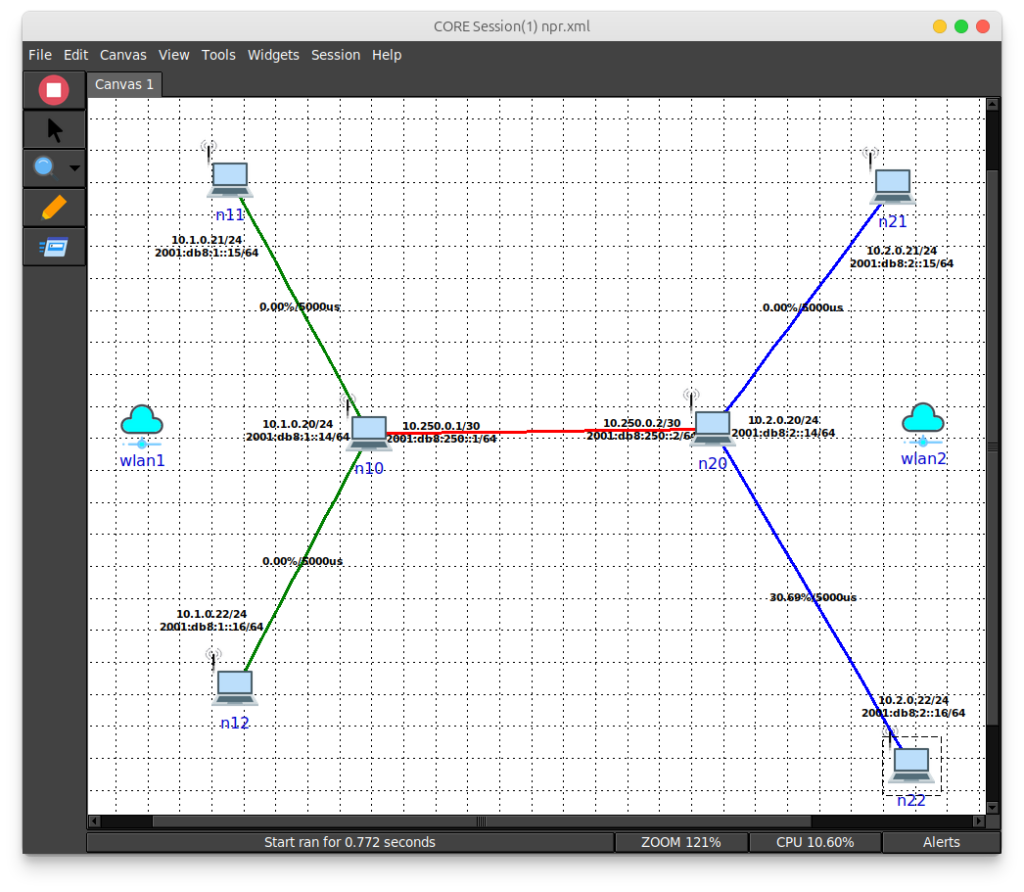

The scenario represents two simplified “NPR-like” sites:

- Left site:

- master node

n10 - client nodes

n11,n12 - wireless network

wlan1(10.1.0.0/24)

- master node

- Right site:

- master node

n20 - client nodes

n21,n22 - wireless network

wlan2(10.2.0.0/24)

- master node

- The two master nodes (

n10andn20) are connected via a wired link (10.250.0.0/30), representing a stable backbone such as Ethernet or Hamnet.

This topology is deliberately simple. It demonstrates how DTN spans multiple subnetworks without simulating TDMA, EMANE, or detailed RF behavior.

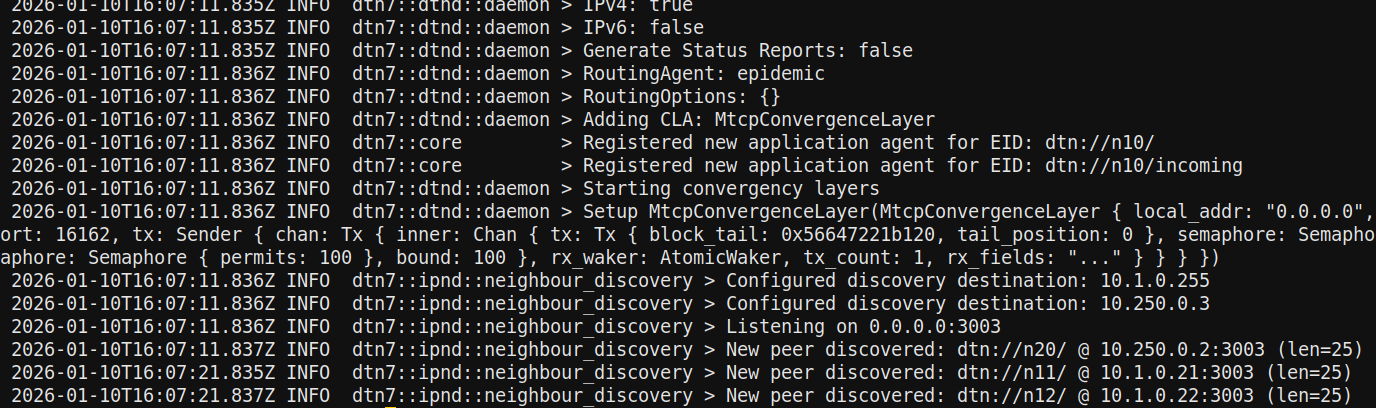

4.3 DTN daemon startup and configuration

Each node starts the DTN daemon (dtnd) automatically when the session begins. The daemon is launched with parameters similar to:

dtnd -n $(hostname) \

-C mtcp -r epidemic \

-e incoming -i 10s -j 30s

At a high level:

- Each node’s DTN identifier matches its CORE hostname (

n10,n11, …), mtcpis used as the convergence layer,- routing is set to

epidemic, - an application endpoint named

incomingis created, - neighbor discovery and cleanup run periodically.

The routing choice is intentionally naive. Epidemic routing floods bundles aggressively and would be unacceptable in a real deployment, but it makes behavior easy to observe without additional configuration.

4.4 Inspecting running DTN nodes

A terminal can be opened on any node (double-click the node or use the context menu).

To verify that the DTN daemon is running:

ps aux | grep dtnd

To inspect recent DTN activity:

tail -n 50 /var/log/dtnd.log

The logs typically show:

- neighbor discovery events

- peers appearing and disappearing

- bundle reception and forwarding

- delivery and bundle cleanup

4.5 Discovering peers

On any node, current DTN neighbors can be displayed with:

dtnquery peers

In this scenario:

n10andn20usually see:- their local client nodes

- each other across the wired backbone

- client nodes (

n11,n12,n21,n22) typically see only their respective master node

This reflects a common radio pattern: edge nodes have limited visibility, while gateway nodes bridge between networks.

Because epidemic routing is enabled, bundles can still be sent to any destination endpoint, even if the sender does not have direct knowledge of the destination node.

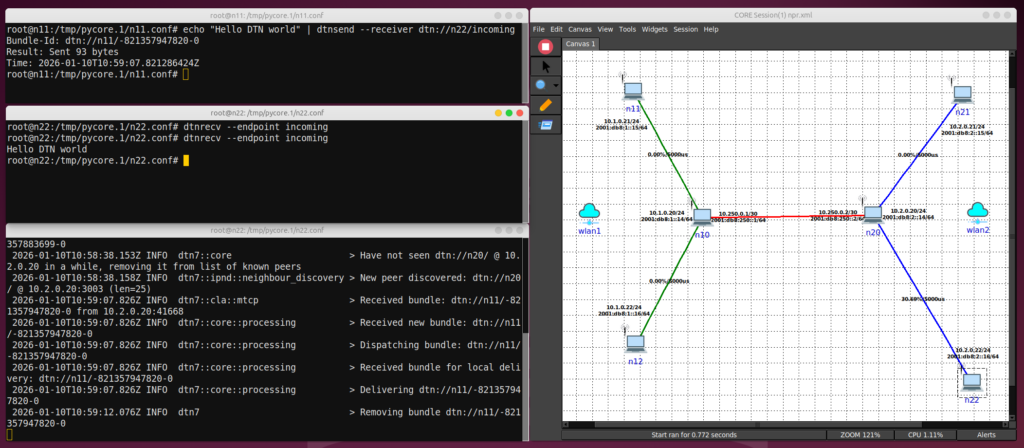

4.6 Sending and receiving a bundle

Bundle reception is intentionally explicit. The receiver must be invoked to fetch and display bundles delivered to a local endpoint. On node n22, run:

dtnrecv --endpoint incoming

If no bundle is waiting, the command exits silently.

Now, on node n11, send a bundle:

echo "Hello DTN world" | dtnsend --receiver dtn://n22/incoming

After sending, run dtnrecv again on n22:

dtnrecv --endpoint incoming

The message content should be printed to standard output.

Intermediate nodes (n10, n20) will log bundle reception and forwarding in their DTN logs.

4.7 Observing disruption and storage

One of the wireless links in the scenario intentionally introduces loss and delay (as visible in the previous screenshots). This causes intermittent connectivity, particularly on node n22.

This instability can be observed in logs and peer lists on n22:

dtnquery peers

Node may repeatedly discover and remove peers as connectivity fluctuates.

A more explicit disruption can be created by dragging a node away from its master in the CORE GUI:

- Move

n22far enough fromn20so the wireless link breaks - Wait a few seconds

- Verify that the peer disappears using

dtnquery peers

While n22 is disconnected, send another bundle from n11:

echo "Stored bundle test" | dtnsend --receiver dtn://n22/incoming

The bundle cannot be delivered immediately and will be stored at an intermediate DTN node, typically n20. Stored bundles can be inspected with:

dtnquery bundles

After moving n22 back into range and restoring connectivity, the bundle will be forwarded automatically. Running dtnrecv on n22 will retrieve it.

This demonstrates the core DTN principle: send now, deliver later, without end-to-end connectivity.

4.8 What this example simplifies

This experiment deliberately simplifies several aspects:

- RF behavior is abstracted to basic wireless links,

- epidemic routing is used instead of realistic routing strategies,

- and contacts are opportunistic rather than scheduled.

Despite these simplifications, the essential DTN mechanisms are visible: persistent storage, hop-by-hop forwarding, and delivery after disruption.

For readers interested in going deeper, the next natural steps are to explore alternative routing strategies, convergence layers, and contact models. The dtn7-rs documentation provides further details on supported features and configuration options.

5. What Comes Next

In the previous sections, DTN was intentionally presented from the outside. The focus was on observable behavior: how bundles move, how they wait, how delivery succeeds even when connectivity breaks. Several internal mechanisms were mentioned only briefly or deliberately simplified.

This was not an attempt to hide complexity. Quite the opposite.

Routing, peer selection, and forwarding policy are the parts of DTN that are the least mature, the least intuitive, and the hardest to reason about. This is true not only in academic literature, but also in practice. At the time of writing, I do not have a complete or definitive answer to how DTN routing should look in heterogeneous amateur-radio networks. What exists instead are partial ideas, experiments, and many open questions.

Even preparing the experimental environment for this article took considerable effort. Packaging CORE, DTN software, and a working scenario into a reproducible Docker image turned out to be far from trivial. The resulting setup is functional, but it is not polished, optimal, or finished. It reflects the current state of exploration rather than a final design, and that is intentional.

Different radio technologies impose very different constraints. A routing strategy that seems reasonable for a small LoRa mesh may fail completely on HF packet radio. Point-to-point UHF links, scheduled backbone connections, and opportunistic contacts all push the system in different directions. It is not obvious how to combine these worlds into a single, elegant routing model, and pretending otherwise would be dishonest.

For this reason, the goal so far has been to build intuition rather than to present solutions. Running DTN, observing how bundles behave under disruption, and experimenting with simple scenarios provides a much better foundation than starting with abstract routing algorithms.

Readers are encouraged to treat the provided CORE setup as a playground rather than as a reference design. Modify the topology, break links, change routing parameters, or observe how bundles accumulate when parts of the network disappear. These experiments are not about finding the “right” answer, but about learning which questions are worth asking.

DTN is interesting not because it is complete and ready to use, but because it points toward new directions for experimentation in environments like amateur radio, where learning by doing is not a side effect, but the main purpose.